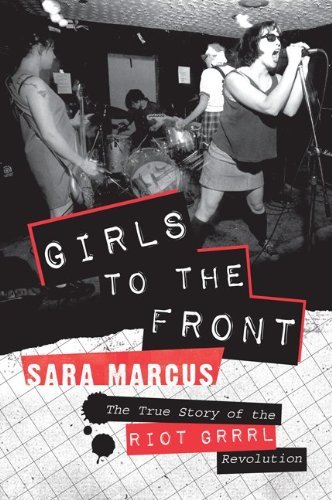

I started going to hardcore shows when I was 15 or 16, probably getting out to one a week during my high school and university days. Ten years on, I’m lucky if I have time to make it to one or two in a year — that distance (and time) has given me space to reflect on the space for young women in what was then, and even more so now is, a male-dominated, hyper-masculine subculture. So obviously, obviously, I bought Sara Marcus’ much-anticipated book about the riot grrrl scene. Punk music, check. Feminism, check.

When I started going to shows, riot grrrl was a punchline, reduced to a fashion footnote for corny photo spreads in the YM and Seventeen magazines my older sister bought — plastic hair barrettes, Doc Martens, pigtails, DIY shirts with shit scrawled on them. It was no longer an actual genre — I’d missed the boat by quite a few years, and it seemed as though hardcore punk (from which riot grrrl was an off-shoot) had settled into a state of true, unshakeable apathy. The punk of the ’70s was about the youth voice; class struggle in the ’80s; consciousness-raising (veganism, grassroots activism, zines about all kinds of political/personal struggles, Hare Krishna) in the early-mid ’90s. But hardcore punk in the late ’90s/early 2000s was about moshing, violence, wearing North Face and Nike Dunks, posturing about ‘honour’ and ‘friendship’ — really, a euphemism for being catty to people who weren’t in your crew. The personal had obliterated the political. It’s still like this, in 2011, except now people wear less streetwear and more black/skinny jeans/plaid. I still love the music but then, as it is now, there were just a few ways for girls to find their way into the community, which boiled down to two main approaches:

- You could be one of the boys: take photos (that was me!), make zines, mosh, maaaaaybe start a band if you were really brave and liked people talking shit about you, or…

- You could be the slut: the girlfriend to some dude in some band or the coat-rack in the back.

Anyway, my own experiences really informed the way I read her book, drawing parallels between our ten-year difference in punkhood. You know, plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose…

One of the big themes was about how riot grrrls (all teenaged girls, really) had no agency or voice when the national discourse turned hand-wringing over their sexualities, their morals, and just about everything else in their lives. It was the ’90s, and there was the March on Washington, the emergence of the Christian right. These days it’s mostly the same — pre-teens slut-shamed in the New York Times after being gang-raped, ridiculous abortion legislation, crisis pregnancy centres, SlutWalks, still about the Christian right and their purity balls and virginity vows (you should read Jessica Valenti’s “The Purity Myth” for more on that).

The most beautiful thing I learned about riot grrrl was that it took the feminist rhetoric of “creating safe spaces” for women and made it real; not just that, but they made it the backbone of their community. It’s easy to be a feminist, hard to be a feminist activist. They went to shows and forced boys to make room in the pit by linking arms in a circle, right up front by the bands, creating a space where women could be part of shows without being moshed over. They started meetings and chapters, where issues of rape, harassment, incest and body image were freely discussed. They lived together, started bands together.

Still, feminism, even a punk version of it, wasn’t without flaws. Most kids who can afford to go to shows, buy records and merch and go on roadtrips aren’t scrabbling in the dirt and feeling oppression firsthand; like pretty much every musical scene since MTV has been an exercise in suburban angst and the odyssey to find belonging with other middle-class misfits. Plus, they are 17, and who can blame them for not being cognizant of post-secondary academics such as Germaine Greer, Andrea Dworkin, Judith Butler, Naomi Wolf, etc., etc., and their concepts on class, race, oppression, privilege, and blah blah blah big feminist words. So yeah, of course riot grrrls were a little oblivious to the dynamics of race and class in their scene.

In any case, what eventually happened is riot grrrls who were feminist (without knowing exactly that they were) became shamed, sort of, for not being up to snuff on said ideas. Anyone’s who’s ever read the comments section on a feminist blog is saving themselves $50,000 in gender studies tuition — pretty much a roomful of edumacated, enlightened gals trying to out-academicese each other. THE PERFECT term for this is “Oppression Olympics.” I can’t remember now whether this phrase was attributed to riot grrrl Erika Reinstein in the book or if I’m borrowing it from an awesome riot grrrl’s blog, but it’s a problem that has not gone away. It can be discouraging trying to remain energized about feminism when it’s become OK for feminists to harp on other feminists for not “owning up to their privilege” or being a white girl and not understanding race relations, or dimensions of class/sexuality/so forth, or shaming people for things they could not have controlled (i.e. having a penis, being white, taking ballet lessons when they were 6 years old), rather than saying, “Hey, women who are feminist and also grew up with privilege can immensely helpful as allies and partners in dismantling all kinds of privilege.”

So, lots of tendrils that still resonate, 15 or 20 years on. More than anything, I mourn the loss of riot grrrl not for its music, but because young women are marginalized in punk unless they are brave enough, have the wherewithal to. I don’t believe it’s a conscious decision for guys in the hardcore scene to exclude women, it’s just a natural extension of the bravado and machoism that exudes from the music. There’s an important lesson here — not just for some now-obscure musical/political scene that came and went within the span of oh, eight years — but for all feminist activists who give a damn and want to do something useful. So to borrow from hardcore vernacular, stop being so fucking negi.

Leave a Reply